CENOTE MELMAK EXPLORATION

Cenote Melmak is a strange place. The cave varies with depth, from sepia-toned hydrogen sulfide chambers at the shallow depths, to sparkling salt water passageways in the deeper sections. However, the most unique aspect of Cenote Melmak isn’t the cave, it’s the entrance.

The access to Cenote Melmak is an old pumping station near mangrove wetlands. We located the pumping station by following an old pipe along a pathway through the jungle, until we arrived at an abandoned cinder block building situated on a cement foundation. The entrance to the cave is a manhole cover in the foundation, with a rusting metal ladder dropping down into a murky pool of water. Melmak was once an open cenote, but was bricked over when the pump station was constructed. Now that the station is out of use, the place has been taken over by bats and roots.

Vince navigates the first chambers of Melmak. It’s full of H2S, which stains the water yellow.

EXPLORATION DAY ONE:

Cenote Melmak is situated on land with restricted access. We are only allowed to be on site until one in the afternoon, which means we need to arrive at the dive site at first light. At five a.m., we packed up the truck and headed out, stumbled through the forest just as the sun was rising, and started our descent around seven in the morning.

Once in the water, the reason that the pumping station was abandoned becomes clear: the water is full of hydrogen sulfide above the halocline, and below the halocline (of course) it is salt water. There’s not much use for either type, and anyone who dares to bathe in water pumped from this station will reek of rotten eggs. The hydrogen sulfide is similar in concentration to the hydrogen sulfide in Pandora, and it appears to have the same bacterial source. Our first thirty minutes in the cave was spent in the haze of the H2S, hoping to drop down into clearer, cooler water.

Vince gears up in the headpool with the bats.

When we finally managed to drop below the halocline, the hydrogen sulfide cleared up and the cave became gray and golden. Underneath a fine layer bacteria, the speleothems were all delicate yellow crystal; the type of rock that glows when light is placed behind it. There was only a gentle current, and the main passage took us over a series of sediment dunes, rising and falling between 25 and 70 feet.

We emptied one reel, and had started on the next when our tunnel ended at a sediment and debris cone. After unsuccessfully attempting to work around it, we hit turn pressure and made our way to the exit. We needed to be gone by one in the afternoon, so it was time to plot our survey and decide which leads to check the following day.

EXPLORATION DAY 2:

Our last day of exploration for this expedition saw us dragging ourselves back into the water bright and early, this time with stages and oxygen for deco. The low visibility made searching for leads difficult, and we spent most of the dive running up against dead ends or looping back onto our own line. Just like in Pandora, every breath and fin movement dislodges delicate bacteria (aka guck) from the walls and ceiling. The lead diver has one breath to look around, and with his first exhalation, guck rains down from the ceiling and he has to move along. This creates time stress, but it’s also sort of fun because the guck flakes are interesting.

Interestingly, while Melmak is near Pandora and has similar appearing bacteria covering every surface, there are no snottites/bacterial straws as there are in Pandora. We are unsure if this has to do with flow patterns, bacterial species, or something else!

“Guck” starts to fall from the ceiling after Vince exhales.

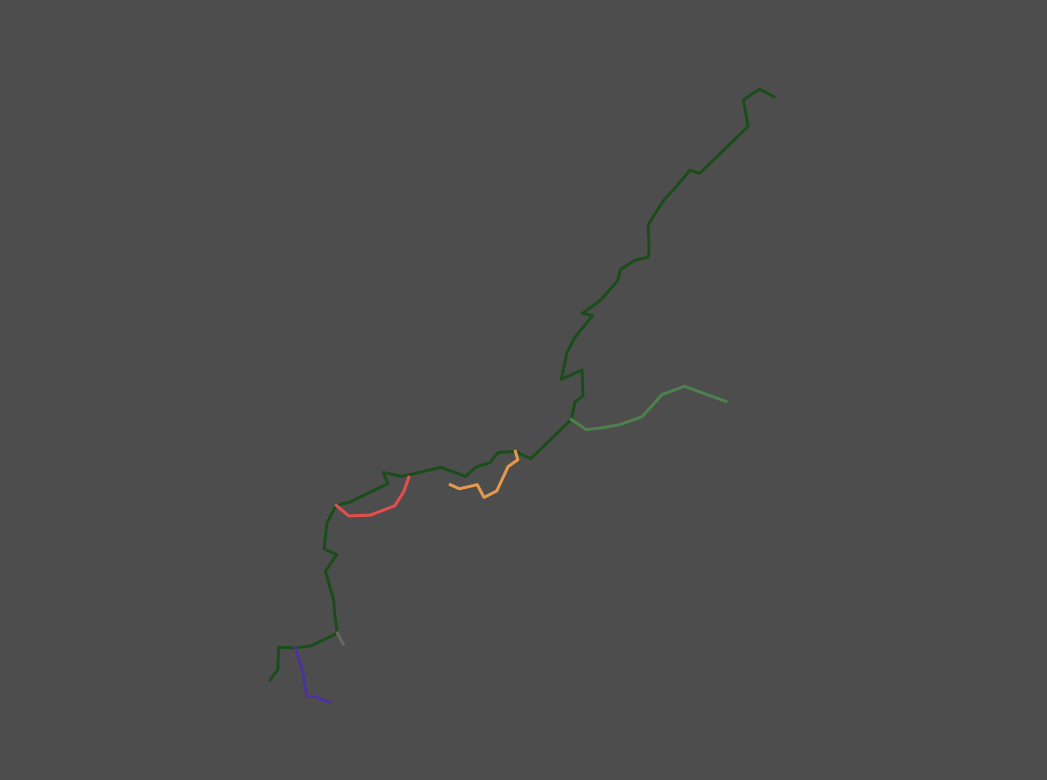

Melmak Survey

The survey of Melmak on the left shows the results of our first two dives. The entrance is from the most southwestern point of the survey. The dark green line is our glorious run the first day, and the colorful lines are the loops and dead ends from the second day. The one exciting lead we found near the end of the dive is the bright green lead heading east off the mainline. This passageway is about 65 feet deep, in blue salt water, and it continues. Unfortunately, we were approaching turn pressure and our time limits, so we had to leave the passage and save it for our next trip.